Why I Attribute

Alan Levine gave me the old h/t (hat tip) for referencing a post recently on AI and copyright law. In a follow-up he recognized my own version of the h/t, the 'via' link, where I credit Clint Lalonde for the find. It makes for a nice neat chain:

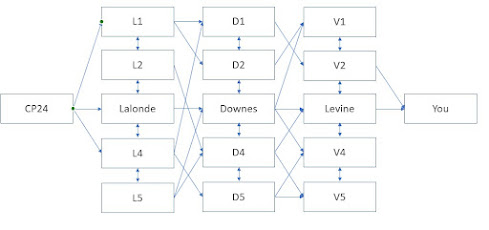

Of course the article had an original source; it came from Canadian Press and was found on CP24, a Toronto news broadcasting station. And it had, after Levine, an eventual reader, who I will describe as 'You'. So in reality, we have an even longer chain:

Now because we all attributed our sources, you (that is, the 'you' referenced in the diagram) can trace the story back to the origin. Of course, you could just look up the URL of the link - but if that became obscured in so way, you could still create that chain.

We could say a lot about that chain.

For one thing, the existence of the chain suggests the possibility of some sort of blockchain that would make it possible to find the source even without an explicit attribution. That's pretty complex, though, and not really essential to any of the points I want to make here.

More importantly, this isn't just a chain of one person passing a link to another to another. All three of Lalonde, Downes and Levine added their own comments. By the time it got to you, you had not only the original story but also some interpretations or perspectives on that story.

Even more importantly, our passing it on represents some sort of endorsement. That doesn't mean we agree with the point of view, or that we're cheering about the result. It means each of us felt that this story was important enough to pass along. By the time you got it, the story had been vetted three times.

We could call this a web of trust, in the sense that you trust Levine, Levine trusts me, and so on. But it really has nothing to do with trust, except perhaps in the very minimal sense that what we're passing along really originated somewhere; that we didn't just make it up.Again, having a blockchain would remove the need for that trust - but so does simply passing along the original URL at each stage.

Why is all this important?

It illustrates a fundamental difference between a federated social network (like Mastodon, where this chain originated, or web discussion boards, where it continued) and what I'll call a mass social network like Twitter or Facebook. There are three important differences.

First, in a federated social network, the story has to take several steps through a chain to reach you. Probably, you don't follow anyone in this chain but Levine. Because the federated social network is divided into different communities, the spread of something like this story is slowed down and doesn't get to you unless it's passed from community to community.

But in a mass social network, it can jump straight from CP24 to you. The story spreads immediately. But there's nobody in between to vet it or add commentary. That's great for publishers, because they can reach a mass audience right away. It's great for advertisers and spammers and bad actors. But it removes any sort of vetting, critical reflection or feedback. You're on your own.

Second, even when the story gets to you via someone else on the mass social network (you might follow @Levine and saw a retweet from @CP24, say) the social network does as much as it can to obscure the chain. You don't see the actual URL, you see a link generated by the mass social network that may or may not take you directly to the source. Even though it looks like the chain is intact, the chain is broken.

And third, a lot of what you see on a mass social network isn't based on any sort of chain at all. Instead of receiving a link that was vetted by three reliable sources, you receive a link that was promoted by the algorithm. This allows the mass social network to serve you advertising, political messages, and whatever else it wants. And when someone sends you a retweet, they might never even have seen the original story, just a tweet they got from the algorithm.

But that's not all.

The federated social network would work the way it does even if nobody gave h/t or via references. The story you read from Levine would still have made three hops between the source and you. You would still benefit from the vetting, some (though not all) of the comments, and the reliability of receiving an original URL.

But what becomes obscured is the fact of the three hops, and the way the story made its way from community to community. And that's important.

Few people have only one follower. Most people have several. Some have thousands. Nobody has millions, as on mass social networks - there's an upper limit somewhere where too many followers doesn't really work on a federated social network (which is why we are very unlikely to see advertising-supported federated social networks).

These followers constitute a community. Each person in a federated social network has their own community, though there's also a wider sense of community where a bunch of people follow each other. There's no simple way to define these communities - just think of them as a group of people who might share a space, an interest, or just a friendship, and who message each other more or less often.

To make things easy, I'm just going to line up Lalonde's community in a single line, like this:

It's represented a single line, L1...L4, but it's actually more like a pool, where the members are all talking back and forth. Lalonde sends things he gets to all his followers - to the members of his community, and to outsiders like Downes.

This pattern repeats itself each step of the way:

And though the connectivity is less dense, there are other messages sent to other communities. So the actual interactivity looks a bit like this:

Of course, it's even messier than this - sometimes the messages skip layers, for example. CP24 sends messages to several members of the Lalonde community, and maybe even to the Levine community, and maybe even directly to you. We may all get the same message from various sources, through different chains, and we add up all their influences on us, to come to a final determination of how to regard the story from CP24.

And to go beyond our federated social networks, somewhere to the left of CP24, there might be a fact of the matter, reported on not only by CP24 but by various sources, official or otherwise, all of which are interpreted and (if deemed important) passed along until the different stories about that fact finally reach you.

And here's the theory...

Getting the message in this way puts you in a much better position to assess the message, evaluate whether it is true, and decide whether to act on it (or pass it along to your own community).

Each community that the message passes through offers its own sort of filter. Each subsequent community regards that filter as both important and reliable. Just as visual signals are sent through several layers of processing in the visual cortex, so also social signals are sent through several layers of processing in the federated social network.

|

| Image: http://webvision.instead-technologies.com/part-x-brain-visual-areas/9-1-primary-visual-cortex-by-matthew-schmolesky/ |

By contrast, a mass social network short circuits this entire process. There are no layers of filtering; it's like getting light signals dumped directly in the brain. It's like a kind of social sensory overload (note that this is an analogy - I'm not going to leap from this to saying 'social media causes anxiety' - that would be irresponsible).

Before social media, we would have expected that professional media would have handled the functions of the federated social network. News stories would be gathered from more than one source. There would be several layers of verification and editing before the story went to print. And people could read and compare accounts from a number of different sources.

These functions, though, have all but disappeared from news media. Because news media depended on advertising, and therefore mass audiences, it came to value engagement over all. The layers of validation and verification were not only expensive overhead, they got in the way of prioritizing engagement.

In academic media the same sort of mechanism was also in play, with the peer review process in place to ensure appropriate method was employed and that the authors preserved the progression of ideas through a social scientific network.

As in the case of newspapers, there was a careful curation of scientific ideas, vetting, follow-up reviews, validation, and editing. This, too, has taken a poor second place to the prioritization of profit by the commercial press, and is something we may regain with (diamond) open access journals, though again, we're going to need to depend on a federated social scientific network to make this work.

And that's why I attribute.

While attribution may be morally good, the reason it's good is that it makes clear these layers of attribution.

The very fact of these layers, and the necessity of of having an article (or an idea, or a 'truth') pass through them, is what grounds our understanding of the world. Without them, it's all just noise.

And when I post links in my newsletter, I want it clearly understood by my readers that what I do is to serve as just one layer in this wider practice. I have my own system of selection, prioritization and commentary. And I think it serves the wider interests of society, even while these interests are being undermined elsewhere by mass media and mass social networks.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your comments will be moderated. Sorry, but it's not a nice world out there.