A Quick Guide to Pyramid-Style Writing

The secret of my success (assuming that I've had both secrets and success) is that I learned to write like a journalist at a relatively early age.

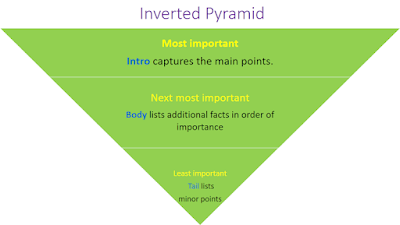

This approach is called the 'pyramid' (or often the 'inverted pyramid'). It allows me to write first-draft content with a minimum of effort to meet any length or time limitation I may be facing. The method is this: put the most important stuff at the top of the article.

It begins with the first paragraph, often called the 'lede'. We want to keep this paragraph short (in journalism the limit is 23 words) and to tell the entire story with that paragraph. The next two paragraphs contain the most important supporting details: why the story is important, how we know it's true, how it work. These are called the 'nut graphs'.

Look at my lede and supporting paragraphs? How did I do?

The story here is often not the 'thing' itself (in this case, the 'thing' is 'the pyramid style of writing') but what that thing did (in this case, the thing 'created my success'). The second paragraph gives me the basic details about what the thing is. The third paragraph explains how it is used.

The idea is based on the premise that you want people to be able to stop reading or writing at any given point and still get the whole story. The shorter version of the story may be less detailed, but it won't have major gaps or lead readers astray.

The Purdue Owl writing lab says structure is the product of the telegraph. "The most vital information in the story was transmitted first. In the event of a lost connection, whoever received the story could still print the essential facts."

As well, reports the Owl, "The inverted pyramid structure also benefits editors. If an editor needs to cut an article, they can simply cut from the bottom. If their reporter was writing in the reliable inverted pyramid structure, the most essential information would remain at the top."

The key to writing in a pyramid style is to make sure each new paragraph directly supports the paragraphs above it. If the earlier paragraphs are leading to or supporting some important information to follow, then the article is 'burying the lede' and making it harder for readers to identify what the author thinks is really important.

How do we know something directly supports something else? There are many ways, and this is where the art of journalism comes into play. It might be a sequence of events leading to the result. It might be a set of premises leading to the conclusion of an argument. It might be the principles and conditions underlying a successful explanation.

Knowing these forms of writing, and knowing how to look for them and to present them, are the most important parts of a journalist's toolbox. Identifying the lede is often the easiest part (writing it is often the hardest part) but then it's necessary to start digging for the rest of the story by asking questions and following leads that support the lede.

The 'who, what, where, when, why and how' heuristic is a useful heuristic supporting that. It allows us to get the comprehensive details of a story and to ensure we don't miss anything important. But it's not used in isolation or for no reason. The answer to each of these questions is relevant only to the extent that it supports the lede or any of the nut graphs.

For example, the 'who' might tell us about cause, it might tell us about motivations, or it might provide an important context that helps explain the story. The 'why' question seeks an explanation as compared to alternative events that might have happened instead. The 'how' tells us the mechanics, the 'when' may mead us to a causal chain, etc.

So far I've typed 641 words and taken about half an hour. For most articles - including online content, blog posts, or short reports, this is everything that's needed. A longer article will need to break the story apart into chunks. But we're still following the pyramid model. The first chunk is exactly what the 500 word article would have been. But now, it will be followed by a few additional chunks, each of which is its own 500 word article with its own lede and it's own nut graphs.

The lede for each of these follow-up paragraphs will something from one of the nut graphs. The idea is to find the most important sub-components of the story (which will be in the first few paragraphs) and treat each as its own story. In these later paragraphs, for example, I am discussing the different types of limitations and how I respond to them as a writer.

As we get deeper and deeper into the story, it becomes less important that a paragraph support all of the paragraphs above, so long as there is a way to link it through perhaps a series of steps to the top paragraphs. For example, one of my 500 word chunks may expand more on the history of the inverted pyramid style. It adds to the information presented in the Owl quotations.

Finally, if you have leisure time, and good notes, you can full out the details of your article. In a news article especially, but in a non-fiction article generally, it should go without saying that everything that is written has t have a source. You can't just make it up. Sometimes those sources won't be explicitly stated in the article, especially if it's short. But they should exist.

When I add sources to my article, I'll either add a sentence or phrase to the upper paragraphs. For example, when I wrote "This approach is called the 'pyramid'", if I were writing a news article, I would extend this to read "This approach is called the 'pyramid', according to leading authority so-and-so." I still want to keep this short; brevity is important here.

Or I might add a paragraph or two of directly attributed quotes containing description, argument or explanation, as I did with the Owl paragraphs above. Or in online writing I might create links in key words, as I did with the word 'pyramid'. This allows readers to follow up with more detail if they want. And it also assures them that what I'm writing as a source; that I haven't just made it up.

Now I'm just over 1,000 words. A good time to stop. It has taken me an hour to this point. At a rate of $0.30 a word (an expert rate (because I'm successful!)) that's $300 (assuming I can find a publisher) (which takes too much time, which is why I post here fore free). Now to spend the rest of the day puttering about to find the next big story and supporting details.

If I'm planning to write 2,500 words, like Doug Belshaw is planning, I'd plan for two or maybe two and a half days. Writing this way, I write about 500 words every half hour, so I'm looking at 5 hours straight writing, and 10-15 hours max compiling notes and doing background reading (or review, in the case of a course) to compile the content.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your comments will be moderated. Sorry, but it's not a nice world out there.