Professors and Bias

A Reader wrote:

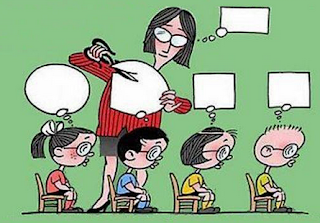

I have seen the shift in politics over the last two years and find myself fundamentally disagreeing with many of my professor's views more often than not. Education is headed down a slippery path of indoctrination. It should be the school's job to teach its students how to think, not what to think.

Thank you for writing. The role of a professor is partially to teach you how to think,

agreed. However, there's more than that. In every discipline there is an

established body of knowledge, and it is their role to expose you to

that.

As well, each discipline has its own culture (or, more frequently,

competing cultures) defining terms and jargon, defining what counts as

evidence, and defining what counts as core questions to be explored. In

my experience I have often found myself at odds with disciplinary

cultures, however, an understanding of that culture is necessary to be

considered competent in the discipline.

Finally, professors will have opinions, and they are expected to present those opinions, especially in the higher level classes. You are not required to agree with them; virtually all professors will welcome a reasoned critique of those opinions (and in my experience, it's that push-back that produces the greatest benefit in teaching for the teacher).

However, not all criticisms are equal. For example, it is

insufficient to say that a professor is biased. First, they will

probably agree, at least in matters of opinion. With respect to the body

of knowledge and disciplinary culture, they will respond that if there

is bias, it is reflected in the entire field of study. It is legitimate

to criticize this, but simply stating that a bias exists is

insufficient, as bias is unavoidable. It needs to be shown that the bias

is illigitimate, that is, that it produces harms, or leads people into error.

You do not need to be an expert, nor fully versed in the discipline, to make these arguments (though it helps). If a professor makes a mathematical error, for example, you need only have enough mathematics education to recognize the error. The same is true of statistical and sampling bias; if a body of evidence is insufficient or unrepresentative, then this is an argument any person with sufficient statistical knowledge can produce.

Note however, it is not sufficient here (or ever) to simply state that these errors exist. It needs to be shown that these errors exist. In the example of mathematics, you would need to specifically identity the error. In the case of statistics, you would need (for example) to state how a sample is biases, and how that bias is relevant to the conclusion being proposed.

All this is the domain of critical thinking. Not every professor can

cover the essentials of critical thinking in every course; it would be

very inefficient. So professors focus on aspects of critical thinking

specific to a disciplinary culture. It is your responsibility to

learn the basics of critical thinking, just as it is your

responsibility, ultimately, to master the mathematics required for the

discipline.

How you master critical thinking is up to you, though most

institutions offer courses. In my opinion, it would be far more

effective if taught at an earlier age, so you are prepared to challenge

professors from the first day of university. If you do not have access

to courses, there are various MOOCs that may help:

https://www.coursera.org/courses?query=critical%20thinking

Comments

Post a Comment

Your comments will be moderated. Sorry, but it's not a nice world out there.