A Year in Photos

Organizations aren’t thinking about the ‘networked individual’ – the networking choices and patterns of individual Internet users. They’re still focused on their own organizational information systems and traditional institutional networks. -- William H. Dutton

Saint John

Andrea and I began the New Year waking up in the port city of Saint John, just down the road from Moncton, where we had spent New Year's Eve watching a basketball game. Our basketball team is not a part of the family compact that owns so much of the industry in our province - to me it represents the future of the province, as something professional, independent, and based in the community. I'm willing to support the team because it's the sort of entity that doesn't just take - it gives back, and knows that without a reciprocal relationship it cannot survive.

I wrote the post Seven Real Signs of Surrender in response to an article that bemoans the commercialization of education but then defends the traditional role of professors and attacks open online learning. But from my perspective there's not much difference between professors pushing product on us or some commercial publisher doing it. The real signs of surrender are found in the passive deference of the university to the commercial imperative. To the extent that the professoriate is failing the community, it is signing the warrant for its own replacement.

Moncton

I spent the first three months of the year developing the core of my Personal Learning Framework presentation and sticking close to home, with a few quick trips to Ottawa and Montreal for meetings. It was a quiet time that allowed me to get in touch with the city again, get out into the winter countryside, focus more on my health and fitness, and throw myself into my new work for the year. More on that as we progress.

I do a number of online talks every year. This talk was delivered online to the Connecting Online for Instruction and Learning 2014 via WizIQ. In this talk, I noted that we are still in a world of mass, of masses of people, votes, ideas - we define ourselves by what we have in common with others, whether it is a language, a nationality, a religion or an idea. These are, I said, the properties of the individual, applied to the whole. It's the way we've always thought of thought, learning and society, as the spreading of an idea.

I think we should think of both learning and of society differently. The sameness isn't what creates learning and growth. The difference, the diversity is what does. It's the interaction that enables us to grow. We don't 'spread the word', we don't 'amplify' ideas - these are the signals we send to each other, but what defines us are the things we do, the way we relate to each other, and the outcomes we create. Ideas, learning culture and society emerge as a result of these transactions; they aren't transmitted through them.

These are hard ideas, but understanding them is key to understanding what works in education and society, what doesn't work, and how each should be structured to achieve the most positive outcomes.

Ashley and Taylor were interns observing as I had my teeth inspected and cleaned, and they were willing participants in my photo-a-day project. They illustrate a point that I've often made, that the best place to learn about some sort of work is in the workplace. And they're learning not by being told, but by seeing and experiencing (and later on, doing, while being observed by experts).

This is why it is important to consider carefully the sort of metrics we impose on open online courses, or indeed, any of our learning systems. Measuring 'course completion' is a poor substitute for watching and evaluating actual practice. I talk about this in my long interview with Juergen Rudolf, and we see it in the french-language course - MOOC-REL - we launched with the Organisation internationale de la francophonie and the Université de Moncton and in my discussion of the origin of the MOOC and theories related to connectivism.

Toronto

Rod and I were in town to meet with Defense department training coordinators, including people from the Canadian Defence Academy and DRDC. I gave them an internal government presentation on the Learning and Performance Support Systems program we were launching; these slides would form the theme for a lot of my talks through the rest of the year. It has been an interesting year for me because as program leader, I am responsible for the overall vision and direction of the program, as well as in attracting interest from potential commercial and institutional partners.

The discussions we had with defence and commercial partners at the meeting illustrate some of the tensions inherent in my own position and also in the nature of the technology we are trying to develop. The default position in education needs to be 'open', for a variety of reasons, and the military people get that, but the default position for them needs to be 'secure'. In a similar fashion, the business model needs to be cooperative, with companies engaged with institutions and students (and with us!) and not simply deriving income from them, but at the same time the bottom line for them is to sell, even in an inherently non-commercial marketplace.

I won't say I have the resolutions to these conflicts. But I think you have to start in the right place. I tried to get at that place with a few posts in February, including one on Economists and Education, and another on Where Government Money Comes From. I think we need to challenge some of the core presumptions about marketplaces - we need to question whether the measures and methodologies promoted by economists are sound (I would say the evidence of the last few years suggests they are not) and we need to question the 'inherent' efficiency of the business sector.

Valencia

I traveled to Valencia, Spain, to present The MOOC of One (text transcript) in which I tried to connect the phenomenon of massive open online learning to the concept of personal learning. The idea was to propose a system where providers offer services to many people, and where people access these services via their personal learning environment.

The presentation was also a challenge to the concept of representation. Traditional learning focuses on the idea that we share a common vision of things. This presentation emphasized the idea that each person's perception is unique. The traditional story of knowledge and perception involves the construction of models or representations, which we then share. But this supposes a separation between cognition and perception; it requires the idea that there is a 'camera' that we turn inward or outward to gather data which we will then interpret. But there is no camera. There is nobody to 'construct' our representations for us. Our perceptions are the result of self-organizing networks, an each one manages the task a little bit differently.

Valencia was beautiful, as expected. The old river bed has been converted into a city-wide park. I rented a bicycle and rode it end-to-end, first all he way out to the see, and then along the shore for several kilometers, and then back through the city centre and out to the open country on the other side. The city is an amazing mixture of old and new, of modern and decrepit, of prosperity and need. I talked about what it is to be One, to be a Valencian, to be a physicist, and the idea that there isn't some standard way to be any of these, but rather, to be one is to be shaped uniquely by the particular environment that is Valencia, or a physicist's lab, or one's own environment.

Tunis

This was my second trip to Africa and my third trip to an Muslim nation, though Tunis managed to be different from any of the preceding. It is a mixture of European influences (French is commonly spoken and the shops are closed on Sunday) and middle-Eastern cultures, with Arabic predominating, the influence of Islam everywhere, and the Adhan ringing out over the city, setting time to a clock that changes every day.

Speaking to an ALECSO board - that's the Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization - in a talk called The Rise of MOOCs I drew together the ideas of open resources, MOOCs and connectivism. In the MOOC part I outlined the history of our work with MOOCs, and then appealed to connectivism to inform the design principle underlying them. As described in connectivism, knowledge is the result of self-organizing networks, and so a MOOC (at least the way we design them) is designed to enable this self-organization process to occur.

So why the open resources? In order for a network to be able to function and to flourish, the entities within it need to be able to send signals from one to the other. These signals are send by means of the creation and sharing of open educational resources. Other approaches to education are focused on the idea that we should internalize or remember the contents of these resources. But connectivism is focused on the way the resources are used in order to create new resources.

Tunis is in the process of self-organization. It hasn't been easy. Important social functions (like street cleaning) have suffered. There are still security problems and so barriers and barbed wire can be an inconvenience. But the Souk is still open and there are products on the shelves. Transit is working, there are police in the streets. The people are getting on with the day-to-day task of living. Everywhere there is life and colour. Tunis, to my view, was a city breathing and learning and finding itself.

Carthage

In Carthage I walked along and undisturbed among the Roman ruins. The city is across a large bay from Tunis, over which, on a causeway, a rickety train runs a regular schedule. It was hot and it was dry and it was sometimes inconvenient to walk the distances between sites, but they gave me plenty of time to think. I saw a seaside park that had not been tended for a decade, a city that had not been lived in for a millennium, and everything in between, from the round harbours of the ancient city to the view from the park and mosque at the top of the hill. Carthage left me breathless.

Tourist buses take people from site to site. They skip the decrepit park, the museum of natural history, and the less accessible parts of the old harbours. There, from a tiny wood shack, a man emerged to tell me about the history of the harbour in broken French. I was the only visitor, perhaps for the day. Where we stood had been completely built up, with boathouses lining both sides. That was before the Romans razed it to the ground and then rebuilt over the same site. And before they too fell. I paid the man a fair price.

The idea of experiencing something from beginning to end, as though it were like reading a novel or watching a movie, is in fact unusual. Sure, some people prefer the tour. They prefer to be taken from place to place in orderly progression. But I have never felt of education as being like that. It's better to mix topics, so dip and dab, to sample that which is interesting, and pass by that which isn't. I've often said that taking a MOOC is less like reading a book and more like reading a newspaper. And the measure isn't how long you spent or whether you finished, but rather, whether you got out of it what you wanted to get.

Me, I value the experiences talking in broken French with men in tiny wood shacks. All the tour guides in the world couldn't give me the same colour, the same flavour.

Istanbul

I think the Grand Bazaar is today focused as much on the tourist trade as on providing local goods and services, but it just reinforces the idea that Istanbul is a city focused on commerce and trade. I visited the Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque, of course, but I also visited the garment districts and trading houses that line the southern shore of the European section. While I was there I called Istanbul "the New York of Europe" and I hold to that description. Its glory may have faded with time, but it remains the continent's eastern anchor and the key to trade and prosperity in the east.

In Istanbul my talk The Massive Course Meets the Personal Learner developed the themes raised in Valencia and Tunis. Again it contrasts connectivist course design with the curricular model. This is a point I have restated many times, and it is core. The content of the course is nothing more than a McGuffin, a plot device to bring the participants together and to get them to engage with each other in an authentic and relevant environment. It is the attractor, the marketplace, the anchor, but the medium of trade, whether it be ideas, contents or tourist trinkets, is unimportant.

The key to understanding this idea is to understand the same environment from multiple perspectives. From the provider's perspective, the course is at the centre, and students and resources flow into it, like they do to a marketplace. But from the student's perspective the person is at the centre, and they interact with one person after another, one vendor after another. The personal learning environment is like that person's wallet, carrying the media and traces of those interactions, and it is owned not by the vendors (who would simply plunder it) but by the person him or her self.

Moncton

In mid-April meltwater and rainfall combined to flood the access road to the office (Crowley Farm Road) as well as the nearby highway. It was the first time this area had flooded. It's easy to quickly blame an unusual rainfall, but if there's anything consistent about Moncton, it's unusual rainfall. No, my take is that the cause is the development taking place upstream - what Moncton is calling the 'vision lands' - in which the area was basically clearcut. Sure, there were studies, but nobody considered downstream, flooding when they planned the site. It has flooded again since and now we're looking at some fairly major renovations to cope with this level of runoff.

When people say "You can't manage what you don't measure," they imply, "You don't value what you can't measure." I did a couple of measurement exercises in April. In one, I evaluated the popularity of MOOCs, not based on gross measures like hits or tweets or whatever, but through discussions of MOOCs on the set of blogs I've been following more or less consistently before, during and after the hype, which shows a more-or-less steady state of interest. In the other I measured the production of posts and accumulation of subscriptions to OLDaily. I am the only person to take either of those measurements.

Measurement is at best an abstraction, it suggests that you already have an objective or goal in mind, and that you have understood the impacts of whatever you are doing. Most of the time, none of these is the case.

Ottawa

In Ottawa , I decided to create a set of photos centred on the Sparks Street mall downtown because the topic of pedestrian malls has been an ongoing matter of debate in Moncton, where I live. I was lucky enough to hit the street at the height of the poutine festival. Poutine is a dish nobody would deliberately invent - it is a most unhealthy mix of french fries, cheese curds and hot gravy (which melts the cheese over the fries and creates a sticky greasy delicious mess). The stands had long line-ups. People obviously don't know what's good for them.

In 2014 I stepped into my new role as program leader, having taken this position to shepherd the Learning and Performance Support System project from conception to implementation. LPSS is developing the technology behind the personal learning environment I have been talking about in my talks. Becoming a program leader puts me into NRC's administrative structure, a welter of policies and procedures, and for this year, a series of training courses.

Ah yes. Corporate training. In 2014 I took half a dozen or so courses, most in person, and some online. A lot of money has been spent on my education this year. I actually appreciate it; it's been an opportunity to grow and develop new skills and talents. I always did enjoy the classroom, I flourish there, and I make it my own think. I have comprehensive notes from all the sessions, taken on a computer (not by hand). But the purpose wasn't to remember the material. The purpose was to create that interaction which is not generally possible in a one-way transfer of information.

Moncton

With the clearing of the snow I was able to get back on my bicycle. This is upper Mountain Road, as seen from the crest of the hill on Homestead Road. It's part of the 60km circuit to Salisbury and back, which is my regular run. I set myself an objective of cycling 2,000km this year. It's an outcome of using RunKeeper, which tracks my cycling mileage. Setting a target pushes me to cycle more.

The point of the cycling, though, isn't to travel 2,000 kilometers. I could accomplish that objective much more efficiently by getting into my car and driving to Toronto and back.

This points to the difference between what we'll call 'systems' and 'networks'. The former, 'systems', are teleological - that is, they are goal-directed, they instantiate values, they have outcomes. They can be (and should be) measured, because they were designed for a specific purpose. But networks, by contrast, are not. There is no 'goal' to a network; each entity within the network has its own goals. It doesn't express or instantiate any values - at best, it is a reflection of a lay of nature or principle from physics.

I had a long debate with Jon Dron over this, because he wants the definition of connectivism to include both systems and networks (the supporters of Action Network Theory come from this perspective as well). my argument against Dron was set up in my post Connectivism as a Learning Theory, in which I argue both that it is a learning theory, but that it doesn't matter because it eschews theories (properly so-called). The bulk of my argument against the systems view is found in my Response to Dron, then Is Connectivism a Broad Family of Ideas and Networks and Systems.

Ottawa

My new responsibilities as a program leader take me to Ottawa several times a year, sometimes for training, and other times for events. While there I make sure to get out to visit things like the National Gallery (pictured), the parks and the streetscapes. Early May is the Tulip Festival in Ottawa, and the city is awash in colour. The tulips were a gift from the Dutch government, thanks for our effort during the war, and each year they send more and more.

Values, goals and intentions run together. Something is of value if it leads to an outcome. Progress toward an outcome is thought to be of value. What, then, is the value of a life? And more to the point, why does it begin, and why does it end? It's pretty easy to imagine - to want, even - that our lives fulfill some sort of purpose. But what could that be? After all, every end, viewed in and of itself, must be judged a failure, for the only outcome is ever the end of life.

I have an answer, little satisfying through it may be. In On Death and Dying: Evolution and Networks I put what I think is the final stake into the systems theory of learning. The reason for death and dying, if we can put it like that, is growth and adaptation. Life cannot evolve without death. This is more true for successful organisms than unsuccessful ones. By reproducing and dying off, we enable each new generation of humans to be different from the previous, and this alone is what allowed us to develop big brains and wisdom teeth.

But of course there is a very big difference between saying this was the outcome of evolution and that this is the purpose of evolution. From the perspective of the end-point, everything can be seen as goal-directed. But when you're in the middle of it, there are no goals. Even the presumption that evolution is somehow an improvement should be questioned. And measuring our adaptation toward some sort of end-state would be absurd.

Education helps us become the sort of thing we are. But what that is, isn't evident until the outcome. So there's no way to measure, a priori, our movement toward that end. Our progression toward death, however, can be measured in minute detail.

I finish my debate with Dron in Networks, Information and Complex Adaptive Systems, and Focus on the Words.

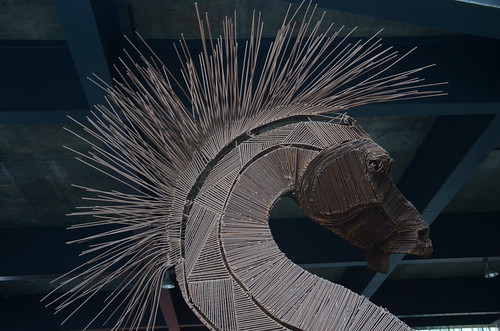

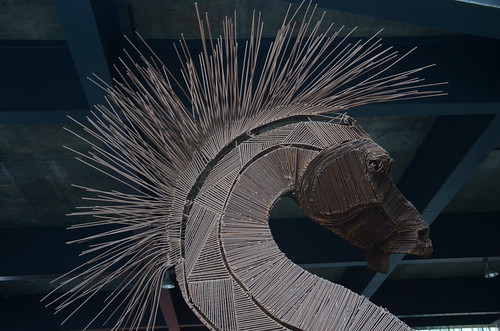

Philadelphia

I took a whirlwind trip to Philadephia where I was at the International Centre at UPenn all day for the MOOCs for Development conference. Here are some conference summaries: Day One, Day Two. This is some of the artwork in the 'Asia Room' of the Center. I didn't get the chance to walk around the city as I prefer, though I did get out to a baseball game.

My talk was a short presentation at a panel, and I talked about The MOOCs Challenge. Much of it was the presentation of the history and structure of MOOCs, though I took the time to focus on the idea of open online learning and the democratization of knowledge.

Most people talk of 'democratization' in terms of elections and votes and sometimes institutions and sometimes legal structures like rights and rule of law. These are all good things, but they depend on a system of government defined by masses and models and structures and organization. think the link between development and democracy is misunderstood. And I don't think you can organize or institute democracy.

We talk about democracy and development as though it is a production problem. And so the role of MOOCs in this environment is depicted as developing skills and getting people into jobs, increasing productivity. But in the cities I've visited around the world there never seems to be a production problem. I see towering glass and steel buildings surrounded by slums, well-stocked stores and malls with people begging on the streets. I see development - and democracy - less as a production problem and more of a distribution problem.

If people cannot participate in the marketplace, they cannot improve their lot in life, no matter how educated they are. And yet a significant proportion of economic and business structures, including those around education, are designed to keep people out of the marketplace. The key to prosperity in places as diverse as Kuala Lumpur and Tunis and Buenos Aires seems to me to be the ability of people to create commerce with minimal overhead - an open space, a mall, an electronics arcade; all these create democracy by creating participation.

When I was an editor at the (democratically run) student newspaper at the University of Calgary many years ago, I put the slogan on the wall: The Price of Democracy is Participation. This seems to create an onus on people to participate. But more so, it creates an onus on society to create the space for participation. The worst thing any agency can do for development is to attempt to own the marketplace. And yet this is exactly the goal of most every company on the internet and in a traditional capitalist society, as owning the marketplace (temporarily) creates profit. At the cost of democracy.

Tübingen

Tübingen is a university city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany - my first visit to the region. According to Wikipediaa, one in three residents is a student. The city eschewed traditional industrialization and so was spared the worst of destruction during the wars, though as a result many of its most elegant buildings are actually fraternity houses. Much of the city is a garden paradise; I stayed in a Bed and Breakfast at the top of the hill and explored the river valley and much of the parks and city core. Hegel and Schelling studies in Tübingen, and knowing this gives me an insight into their philosophies (especially Schelling's).

The purpose of my visit was to deliver a keynote to the International Workshop on Mass Collaboration and Education, and the purpose of my presentation was to draw out the distinction between Cooperation and Collaboration.Why this topic? For one thing, people frequently talk about learning and collaboration in the same breathe. You cannot attend a workshop without doing small group work, and the purpose of a lot of learning is to develop a student's ability to work in teams. But from my perspective, a lot of this is making people less effective, and the theory behind collaboration runs against my own network and connectivist perspective on the world.

To put the issue in a nutshell, collaboration is based on commonality, while cooperation is based in diversity. Collaboration is about building models, structures, and most importantly, shared understandings and shared goals. I'm not sure this is even possible, and collaboration generlly tends to descend into the imposition of order. In cooperation, by contrast, working in teams is depicted as a type of interaction among equals, where each has his or her own understanding of the world and their own objectives and purposes. Cooperation is an exchange intended to create mutual value.

That, really, should be the idea of education in general and a university in particular. Nobody would imagine a university where everyone shares the same beliefs or ideas (with some notable exceptions) and students, for the most part, do not engage in education, especially higher education, in order to be indoctrinated. They are each there to pursue, as Mill would say, their own good in their own way.

One would think this is chaos, but this is where the natural setting (and the understanding of it by people like Hegel and Schelling) come in. Order does not require collaboration; it does not require that each person share a common set of ideas or goals (or, indeed, any ideas or any goals at all). Nothing is more organized than nature, nothing seems to exhibit more of a weltgeist, and yet there is no organization.

I took copious notes from the workshop: here's Day One, Day Two, and Day Three.

Stuttgart

While I was in Tübingen I took a side-trip to Stuttgart as well as a bicycle ride up the river to Rottenburg. I also took the time to do an online presentation to the Digital Research Methods workshop for e-teaching.org called Digital Research Methodologies Redux.

It was a reprisal of some ideas I had discussed in a paper the previous year called Against Digital Research Methods. The idea is that the standard model of research practiced in our field is a slightly modernized version of the deductive-nomological (DN) method - that is, it's an approach where you create models or representations and then test them by making predictions and projections. The problem with this approach is that it presumes that there is a separation between the theoretical framework - the model or representation - and the entity being studied.

Or, to put the same point more bluntly, we read the theory in to whatever observations we are making, and then use the observations to confirm the theory. It's like the 'Face of Jesus' phenomenon. We recognize the supposed face of Jesus on the surface of Mars because of our prior belief in Jesus, and then use the existence of that face as evidence for our belief in Jesus.

My own approach to research is to think of it as more like discovery or literacy. By immersing myself in the subject material, making connections, creating artifacts, and communicating my experiences, I put myself in a position to recognize patterns of perception - not to construct those patterns, but to create, through a process of growth, this capacity to 'see' or 'speak' in this environment.

When I visit a city for the first time (or the fifteenth time) I am engaged in exactly this sort of practice. To theorize is to presume there is some sort of plan according to which the city and its inhabitants are structured. And there may even be! But it is folly to presume that. But by abandoning this pretense, I place myself to interact with the streets and people, the artifacts and architecture, and to understand what the people of the city say to each other and to me.

Moncton

We were hit with tragedy in Moncton when a shooter gunned down three RCMP officers. The local newspaper kept its coverage behind a paywall so I spent several days keeping people up to date via the Moncton Free Press. This had me glued to all of social media around the event, which I covered in The Shooting and Social Media. Without proper local coverage (television news is on a provincial or regional basis) people had to figure out for themselves what to do. The City and the police used social media quite well, and for the most part nobody noticed that the Times & Transcript had made no contribution to the community.

I also spent some of that same period of time writing my post New Media. It reflects some of the anger I felt about how we were very much let down by traditional media. We have new knowledge ("shifting from knowledge as remembering to knowledge as recognizing"), new students (who create and produce their own learning), new software (beyond adaptive, software becomes intelligent "by associating data, recognizing patterns, and making inferences"), new media ("interactive multimedia offered through multiple screens and multiple channels, all at once"), new writing, new internet, new parents and new universities.

This was probably my best overlooked paper of the year. But that's OK. There are bigger issues. Like Pollution and Propaganda. Like the Achievement Gap, development, and inequality. Like the Facebook Research that consists of manipulating people's emotions. All of which continue to be 'explained away' by traditional institutions and media (who don't, it seems to me, want to deal with them).

At the start of July, colour me angry.

Greenwich

Greenwich is a study in contrasts. It is, of course, the home of the Royal Observatory, where standard time is, um, standardized. It is also the home to palaces, churches, and the University of Greenwich. Through several days I explored the area thoroughly, looking for the contrasts between the formal and the informal, looking for life, both between the lines and outside the lines. The park is probably one of the world's great parks - to my mind it ranks with Frogner Park, Stanley Park and Central Park. And the city itself feels comfortable, well-worn, and well lived in.

I was in Greenwich to do a set of three talks, which I combined to form a single set. For my three talks I did something I had tried once before, but on nowhere near the same scale. I took the previous few months of OLDaily posts, organized them into logical categories, and then used them as the raw materials for my talks. Each slide corresponds generally to one OLDaily post. The result is a talk that is completely up-to-date, clearly well-researched, and yet pulling insights, examples and observations that the standard literature won't provide. I later converted each into an article (and the set of three are being translated and published in China).

For this first talk I set up a response to Diana Laurillard's question, "What is the problem for which MOOCs are the solution?" In my talk Beyond Free - Open Learning in a Networked World (transcript) I offer the response. I have always intended open online learning to address issues of access. But it's not just an issue of access to higher education. I mean access to the wider benefits of society. And when I turn the question around - "what is the problem that universities are intended to solve?" - I find that they play an important role in preventing access to the wider benefits of society. They create costs, they create debts, and then the benefits digital technologies promise never seem to materialize.

Where we are seeing a sea change, by contrast, is outside academic institutions and commercial publishing. We are seeing what Martin Weller has called 'the open virus' - the spread of people creating and sharing learning and resources despite the best efforts of the commercial sector. But what has happened more recently is that just as we celebrate the ascent of open education in the form of the MOOC, it is co-opted and deformed by the commercial sector, becoming the antithesis of what it was created to be. We need more than just free resources, therefore - we need the open society of learning and development that they promise.

Instead of simply recreating the free course, we should be building the structures for things like mesh networks - in other words, the infrastructure around which a free society can be built. The idea of the MOOC is not just the idea of open resources, or even open teaching … it’s about living openly. It’s not about teaching it’s about sharing the process of thought and inference and discovery with those around you. Open content, open access, open learning… these are not only a part of democracy, they define democracy, and our system of free and open government depends upon them.

London

The second talk, Beyond Institutions - Personal Learning in a Networked World, took on the topic of models and standards. I confess that I approached my second talk, at the London School of Economics, with a bit of an attitude. I gave the talk only moments after seeing this display in the window - the t-shirt, if you can't read it, says "More intelligent than you since 1895." Now my other confession for this paragraph is that I don't feel I take a back seat in intelligence to anyone. And it is this attitude, expressed in the t-shirt, that has been the cause of so much misery over the years, the supposition that status, wealth and privilege reflect some sort of personal superiority of ethics and ability.

In London, I decided to explore the perfect counter-example to that proposition, the Royalty. So for the first time after many visits to the city, I wandered through the grounds around Buckingham Palace, seeing the building for the first time. There is obvious wealth, status and privilege there. And no shortage of beauty and elegance either. The gardens surrounding the palace in London aren't quite up to Greenwich standards, but they (along with Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens) add a necessary element of green to the cityscape.

In this talk I begin by attacking the foundation of economics itself, the idea of models and standards. What happens is this: people decide that students (or society, or whatever) needs a particular outcome (often these outcomes are self-serving). They then devise a 'model' or 'standard' designed to produce that outcome. These models then become the ideal that institutions are based on and that defines success and quality in the domain. But what's missing in these models (as David T. Jones says) is bricolage, affordances and distribution - in other words, the human element.

The values institutions bring are management organization and control. But I respond that not only are these not needed, they are the wrong values. They are not needed because people can manage, organize and control themselves - my photos are full of examples of this. And they create the wrong kind of learning, learning that is best personalized rather than personal. The abstraction is not the reality, and when we design for it, we design away from reality.

The right model, I argue, is to do away with models altogether. The way forward is to reclaim education (and more broadly, to reclaim society), to change it from something that is 'designed' for us to something that we create and we design. And I draw the connection between self-organization in neural networks and self-organization in social networks (the Siemens answer - the networks reach out and entangle each other; the Downes answer - networks interoperate through a process of pattern recognition).

Canary Wharf

Everywhere I went in Greenwich the towers of Canary Wharf loomed overhead from across the river. I finally took the train over and wandered around the ground on a Friday afternoon, watching the rich and privileged cram the outside barns and taverns, watching each other get lit among the glass and steel towers and artificial gardens and artwork that tries very hard to bring humility to a city that knows none.

In my third talk, Beyond Assessment - Recognizing Achievement in a Networked World, I tackled the issue of assessment for an e-portfolios conference. I began with the idea of 'faking it' and raised the question of what credentials were intended to achieve in the first place (beyond, as I've outlined earlier, creating new barriers preventing people from reaping the benefits of society). The issue of measurement (that economists' dream) permeates education, yet when when we look at what we want from education, and what we measure, it's hard to find a wider gulf. This becomes even more perverse in the era of social networking as each of us leaves a veritable digital trail making it clear for anyone to see whether we have the credentials we claim.

At the core of this is a misrepresentation, and possibly an misunderstanding, of what ti means to know or to learn. The credentials people would have us believe that it is to demonstrate outcomes, to show the successful capacity to remember this or that or do this or that. But 'to know', from my perspective, is 'to recognize', and to learn is to become the sort of person who recognizes. And if we reflect for a moment, any other account of knowing must be the exception rather than the rule. Here's the transcript of my talk.

It is ironic that the Holy Citadal of Measurement decorates itself with desperate and decorative art. We can see with a glance what the bankers with the finest tools of finance and economists couldn't recognize in a year. The bottom line for everything, we are told, is value - the law of supply and demand base price on willingness to pay, but this is a fraud, an artifice. Just like their city.

Interlude: How to Survive Air Travel, For Real.

"If you need something special, just ask, and then wait really patiently. If they say they can't do it, it's because they can't do it; asking a second time won't change that. If they appear non-responsive, it's because they're trying to do what you ask - the computer system is slow and awkward and it takes time to change a flight, move a seat, etc. Waiting patiently while any airport service staff does their job is the key. Here's the trick: generally, there's nothing you can say that will speed up what they're doing, and most anything you say will slow it down. Just be clear, state what you need once, and accept the response for what it is."

Also: My Top Tools for 2014.

Gatineau

When I lived in Ottawa what we now call Gatineau used to be the city of Hull, and while Ottawa was about elegance and government, Hull was about factories, the working class and late nights at the pub. In an effort to share the wealth a bit, the government built two large complexes across the river. It has taken a long time, but around them now a pleasant cluster of restaurants and services has emerged. I visited the city to give a talk to what used to be called the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) but which is now a branch of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. It's still (some of) the same people, though, and despite changing priorities on Parliament Hill change takes longer on this side of the river.

My talk was called Free Learning from a Development Perspective, and it looked at how free and open educational resources can support cultural and social growth. To begin, I've added to the traditional definitions of 'free' (as in 'beer', and as in 'libre') an additional criterion, 'open' as in 'door'. It's the aspect of free and open content that has to do with access and opportunity. The way this applies in education is to shift the focus from content to engagement. Knowledge, which I've talked about before, is the organization of patterns of neural connectivity, and learning is the growth of those patterns, which can only happen with engagement.

The way this ties into development is that what we are trying to do is to create in the individual and in society effective conditions for network grown, and to my mind, these are the conditions that enable a network to be robust, reactive and dynamic - the conditions that allow, in other words, a network to learn. And so I outlined these, as I have in so many previous talks: they are autonomy, openness, interactivity and diversity. The remainder of the talked focused on the policy and development implications of these principles.

There's an argument in philosophy called the Chinese Room example. The idea is that you put some people who don't speak Chinese into a sealed room. You send Chinese characters into the room, they look the characters in a big book, and send the appropriate response as dictated by the book. The argument, as stated by John Searle, is that the person doesn't really understand Chinese. But what if it's the person's brain, and not the room, producing the response. This is the point of the discussion of the Chinese Test example.

We always seem to want something more from these systems. What more could we want from the Chinese test? What more could we want from development? Why must be be directed toward some end over and above the system itself?

La Pocatière

This August Andrea and I drove to Toronto and back. The, ahem, excuse for our trip was to attend the Miller family reunion - that is to say, the family on my mother's side. That's my Irish half - my Aunt Donna has been building our family tree and this side of me has Irish relatives going back as far as we would find. But, of course, I'm Canadian, which means any excuse for a road trip will do.

And one of the things I really wanted to do was to catch a couple of Blue Jays games. They were, as it turned out, the only Jays games I got to see all year, so the choice was well taken. We also intended to visit Bill and Shirley at their new home in Elora, but we didn't make it (I feel badly about that, but we were wiped out from the driving). Anyhow, we stopped to take a break at La Pocatière on the way back - it's in Quebec, on the south shore of the now-massive St. Lawrence River, and (in the summer at least) a little bit of paradise.

Kildare

Where people find paradox, I find harmony.

Each August we take a few weeks to camp in Prince Edward Island, at Jacques Cartier Provincial Park in Kildare. Though I have been increasingly connected through the years while camping, it is still my escape from the rigors of work and city life and a chance for me to connect with the things that are important to me. The north cape region of Prince Edward Island isn't the same tourist draw the more scenic central and eastern parts of the province, but gently rolling hills and farm country create scenes of almost perfect harmony.

Through the years I have also used this time to cycle out in the country, and as time has gone by I've become a more expert cyclist. Well, maybe not expert. But this year I participated in the Medio Fondo in Charlottetown (the Medio is a 100km route), and the following week, managed to complete a 120km ride to Richmond along the Confederation Trail and back along the highway. The photo above is from that trip, it's Oyster Creek, about 20km south of the camp, and one of the most perfect landscapes ever.

I sometimes refer to this, but I think it's important to understand the convergence of all of these things in my philosophy. When I see the flat water and environment in balance like this, I see the same landscape I see when I look at the thinking brain, the well-ordered society, the learning environment, or the sense of self. Whether I engage in cycling or photography or writing or traveling or talking, I am engaged in fundamentally the same activity. Sure, I could experience all these as a spectator, having everything done for me - but I can't imagine that as a life.

While I was camping my visa applications for fall travel were going south. I was eventually able to travel, but my trip to Colombia was impacted, and as a result my planned visit to Medellin became a virtual presentation from my living room.

My talk was entitled The Challenges (and Future) of Networked Learning and addressed themes that should now be familiar: the structure of MOOCs, the nature of connected learning, and the value of open resources. In this talk, though, I wanted to drill down into the idea of networked learning itself, because it's not the same as traditional classroom learning. As Wikipedia says, "Networked learning is a process of developing and maintaining connections with people and information, and communicating in such a way so as to support one another's learning. The central term in this definition is connections."

It's funny. Diego Leal asked me to address, among other things, the POSSE model. He meant of course, POSSE as an acronym/abbreviation for Publish (on your) Own Site, Syndicate Elsewhere, but I thought he meant the POSSE model which describes owned, bought and earned media (POSSE = produced, owned, seeded, social, earned).What resulted though was a alk that connected the core ideas of the skills people need in order to be able to learn in a network environment, which I've described in the past as the 'critical literacies', and the ability to 'own' one's own learning.

The relations between these things matter. The network society doesn't exist without people who are capable of functioning in a network. Full freedom and empowerment do not happen without a network society. You can't just put something into the system and expect an output: it has to constantly grow, evolve, connect and reconnect. The same is true for people.

Moncton

It's hard to be back in the city after being in my happy place.

Probably my most sad moment back in the city was my Trip to the Bookstore. To be sure, I did find a good discussion from Ray Kurzweil on pattern recognition, affirming once again that I am on the right track, though Colin McGinn called it "obviously false" and the New Yorker called it "dubious". I find much of what I see in traditional print dubious. At the bookstore I saw religion in the science section, a 'Middle East' section consisting solely of Israel, and a diminishing level of intellect in what was one the literary centre of the community. And I know (as I say in MOOCthink) that simple stupid neurons can learn.

New York

I'm rarely invited to speak in New York, but several times now I've had a long layover on my way south, and the same happened again this year. My intent had been to visit Brooklyn, but instead I found myself walking up Broadway past 108th street. It was a walk that took me past Times Square and Columbus Circle, the now modern landscape described as "the gaudiest, the most violent, the lonesomest mile in the world" in the 1950s radio show Broadway is My Beat.

For the last number of years I have been a consistent listener of 1940s and 1950s radio dramas. They call it the Golden Age of radio. I was initially attracted by the Philip Marlowe mysteries, but since have listened to hundreds of episodes from shows as varied as You Bet Your Life, Gunsmoke, the Adventures of Johnny Dollar, and Bold Venture (to name just a few). They paint a picture for me of the world as it was just before I was born - indeed, of the environment into which I was born.

It's fascinating on so many levels. One of those is that the primary purpose of radio, it seems, was to promote smoking (come now, does the title of the series 'Gunsmoke' make sense in any other context?). And yet there was an overtly social and political subtext to these serials, both in the content and in the (non-smoking-related) advertisements, promoting the idea of a free, democratic and inclusive society. We are all familiar with the social and political upheavals that took place in the 60s. I cannot help but feel the progressive messages in these shows were a primary cause.

Pereira

I am constantly amazed by how wrong our perceptions of countries outside the 'developed world' can be. Pereira is a city of more than half a million in south-central Colombia, part of the country's coffee growing region (and home to some very good coffee). It is also a modern industrial city with traffic, malls, high-end stores, all manner of services, kind people, modern media, and much more besides. It's in this context that Diego Leal speaks about Building a Learning Network.

In Pereira I explored the question of perception and communication in in talk Learning and Connectivism in MOOCs. I'm not the first to say that learning about the world is essentially like communicating with the world, or learning the language of the world, but I think I say it in a new way, because my understanding of language and literacy are different.

The traditional conception of language and literacy is that they are basically the acquisition and mastery of a certain body of facts or rules. I'm reminded today of how Kathy Schrock complained of my criticism of her account of the many different literacies required in the 21st century. But we don't 'read' the world (or even a page of text) via the acquisition of facts or memorization of principles. I know some people want to say that 'content knowledge' is prior to literacy. But they don't undertsand literacy.

So in this talk I looked at the six critical literacies in detail (they are: syntax, semantics, pragmatics, context, cognition and change). I considered each of them as a way of looking at the world, a way of organizing learning, and a way of structuring a MOOC. What's important here is that even this taxonomy is itself an approximation of a messy, fuzzy and complex process (when we think of Wittgenstein's argument that "meaning is use" we can see how these overlap and interact with each other). The key here is that the ways of communicating and the ways of perceiving are one and the same; there isn't a 'perceptual layer' and a 'communications layer'.

In the same way, when I explore a city, discover a city, and photograph a city, I am at once both perceiving the city and communicating with the city. Some aspect of the city - the parks, the statues, the memorials - are overt acts of communication. But I see the same thing in every corner of the city - I see people talking to each other, creating and sharing, doing and learning. And when I take my photos and share them back, I'm reflecting what I've heard and understood.

Riyadh

Travelling to Saudi Arabia was a highlight of my year and I made the most of it, taking dozens of photos of Riyadh from all angles. Being able to see the country first-hand changed many of my impressions, reinforcing some and completely contradicting others. The city itself is sprawling and populous, clearly a desert setting, but also a mixture of modern industrial and traditional.

It was in Riyadh that I introduced the elements of our Learning and Performance Support System in detail for the first time. The program has five major projects: a resource aggregator, a cloud data system, a personal learning record, a personal learning assistant, and a competency recognition system. These could be designed as a platform, the way Facebook or Coursera are, but the purpose of LPSS is to build a personal learning envrionment.

This talk was more technical and more tool-based than my other talks from the year. If thought of by itself, it seems a bit sterile. But what I tried to reflect is the background that informs this design, from the idea that we 'see the future by reading the signs' to the idea of learning as a network phenomenon. LPSS is intended to be the technical realization of that idea.

What I found most interesting about the city was how easy it was for me to adapt. I've always spoken of the Adhan, and Riyadh brought its welcome return to my day. I was able to see more directly how the rhythm of prayer brings a rhythm of life to the city (and even to observe the ritual's calisthenic effects). The division of men and women began to feel natural, the clothing was more comfortable, and the ways of relating to people more cultured. Oh I know, it's nowhere nearly that simply. I'm just reporting on how it felt.

I met many interesting people in Saudi, and took notes from talks by Bader Alsaleh and Steve Wheeler.

Curitiba

I wasn't sure I was going to be able to enter Brazil, but once I was able to get through the visa process I was treated to an elegant city of almost two million set on rolling hills with parks, stately buildings, busy malls and quiet residential areas. It was my first visit to Brazil and reinforced my understanding of Brazil as a country of contrasts, of wealth and development alongside poverty and need.

What really interests me is the detail required to make these complex networks work. Flying over Sao Paulo I saw a sea of skyscrapers, as far as the eye could see. Walking through Curitiba I wondered about the roads, the water and sewer systems, the electricity - all the pieces that we need to put together to create a recognizable whole. You could never plan the overall state - it would be beyond human comprehension to do so. And yet we can produce such complexes.

I begin my talk Creating a Learning Network by describing in some detail how I created Ed Radio by connecting RSS feeds with Winamp and Shoutcast and cron jobs. I dove deep into the technology, knowing that people wouldn't necessarily follow it, but emphasizing as I went along that what I was describing was a way of thinking and approaching design, not offering a recipe. I then started the process over again, describing how I built OLDaily, and then, finally, how I built the MOOC.

What emerges from these accounts is an approach to technology in general. Because it's wrong to say that 'technology is just a tool'. The technology we choose really does matter. There are many ways to build radio stations, newsletters and online courses - but the tools we use to build them define what we can do with them.

I also experienced food poisoning in Curitiba. It wasn't a major case - I had much worse in Brussels - but it again underlines the fact that it's the small details that matter more than the grand plans.

Iguazu Falls

Take Niagara Falls, give it two stages, and then for good measure add a couple hundred other spectacular waterfalls in the same area, and you have something maybe approximating Iguazu Falls. This was truly a sight not to be missed; I spent all day at the site wandering along the Brazilian side of the river from the very base of the falls to the placid river above. I was drenched, dried and then drenched again.

Cuidad del Este

I can't imagine all of Paraguay is like Cuidad del Este. It took me a while to figure out even how to enter the city. The way it worked was, I was taken by taxi from Iguazu to the Duty Free shops in the city. I went through the shops and out the mall entrance to find myself in the chaos that was Cuidad del Este. It was to me a stark stark warning about what can happen when poverty and a breakdown of order exist. As I walked down the crowded sidewalk vendors came at me with crackling tasers, offering them for sale. The fact that I would need them gave me pause for thought.

I nonetheless pushed beyond the chaos because I wanted to see the real city beyond the border crossing. There are the makings of a nice and pleasant city, but the polluted river and pond, the cracked and broken sidewalks, and the make-do nature of just about everything made it difficult to see the possibilities. Still, I saw people playing football in the field, people pausing for a beer or a coffee, people going about their everyday life, golf-cart taxis, motorcycle taxis.

Moncton

This is Victoria Park in Moncton, about a block away from where I live, in early fall, well in bloom, the plants taking over after the gardeners have left off. I don't spend enough time in Victoria Park, but it's one of my favourite parks of the city, and obviously very photogenic.

I probably can't stress enough times how much my own philosophy is influenced by wilderness and nature - and even my little artificial constructs of nature, like this. For example: we see a forest here, say. And we see the individual flowers and trees and a trellis. It is convenient to talk of the forest, perhaps, but does it make sense to talk of the forest as being distinct from the trees? Of course not - to do so would be to commit what Gilbert Ryle calls a category mistake.

In logical positivism, the idea was that these entities - things like 'mind' and 'belief' and 'desire' could be constructed from experience via logical inferences from sense-data. Accordingly, these ultimately, to Ryle, became dispositions to behave in a certain way. But they cannot actually be derived from sense data. In my short post on Positivism and Big Data I illustrate the fallacy of that idea. The things we think we derive from the date were embedded all along in the way we describe the data.

And so if we actually look at Victoria Park, the real park and not just the representation, we find that the trees aren't very close together at all - their appearance as such is just an illusion created by the photographer. So if we want to talk properly about Victoria Park, we should eliminate the term 'forest' from our vocabulary, because there isn't one. A lot of our understanding of nature is like that. Everything from the theory of Gaia to the 'invisible hand' of the marketplace to things like 'desires' and 'beliefs' are not, as we would think, separate stand-alone entities, and it's possible they don't even exist.

This is the basis for my discussion of Constructivism and Eliminative Materialism with Fred Bershears. The core entities of constructivism - the models or representations that are 'constructed' in the process of learning - are like that, I argue. Like the trees in the 'forest', there is no construction, and the trees don't 'represent' anything. When we engage with nature - as in a forest - or with people - as with park designers - we are engaging directly. There isn't a 'symbol system'. There isn't 'meaning'.

Port Credit

In the 8-hour layover in Toronto traveling from Moncton to Yerevan I took a taxi to Port Credit, rented a bicycle, and made my way through Oakville to Burlington and back along Lakeshore Road. It started out calm and serene but turned into a typically windswept October day as I raced just ahead of the rain. Somewhere in Oakville on the way back, I reached my target of 2,000 kilometers for the year. I'm proud to have achieved that, but the experience of the ride goes far beyond what the number can express.

Yerevan

I commented at one point that there's more public art in one city block in Yerevan than there is in all of Moncton. Though I visited in the fall, well after the summer café season, it was evident that Yerevan was a city devoted to its heritage and its culture - and to slowing down and enjoying an afternoon on the patio outside. Armenia is not a rich country by any means, but it is a gentle country, one I would visit again at a momentès notice.

This trip was sponsored by KASA, a Swiss development agency, and was focused on capacity development much more than research presentations. That said I wanted to provide the best of both worlds, and so added a fourth to the 'Beyond' series of talks I gave in the summer, presenting Beyond Borders: Global Learning in a Networked World.I also did a workshop on how to create a MOOC.

"We speak many different languages," I began. "This is both the challenge and the opportunity." Of course I'm not talking only of Armenia, Russian and English, but also the many ways we see and perceive the world. As I've discussed before, we use a wide variety of objects to communicate with each other - not just words, but art and statues, buildings and parks, and music and culture. In this talk I look at the point of this communication, and examine the idea of achieving harmony through diversity.

That's why free learning (as I've come to call it over the years) is as much about attitude as it is about access. It's not simply sharing for the sake of sharing, it's not simply broadcasting some message for all to hear, it's about being open both in sending and receiving, taking care not only to freely share your own knowledge but also to learn from that of others. We create our society and our culture together, each person contributing his or her unique perspective.

That's what our MOOCs are. They're a formal recognition that people have different destinations, different tastes. They are an approach to education based on an understanding that knowledge varies according to these differences. And it expresses the principle that networks – communities – are stronger with multiple diverse perspectives. Harmony isn't (only) about balance - it's about mutual reinforcement. Glass, stone and steel mesh together far better than glass alone or steel alone or stone alone.

Tbilisi

Tbilisi is a grand old city with a historic central core that remains largely in ruins thanks to (I assume) large earthquakes that hit in 1992 and 2002. It was also the site of the 2003 'Rose Revolution' and as I walked around the city I recalled Eduard Shevardnadze saying "I did not become president of my people in order to kill them." Would that more leaders had such regard for their nation.

Georgia struggles, especially in the dark and chill of December. As in Armenia, the only way to cross major roads is via pedestrian underpasses. As I left the train station I entered one of these to get to the city centre. It was cold, dark and muffled. In the maze-like structure was stall after stall of vendors selling used clothing. People did not move a lot; they spoke in hushed tones. Oh, things are better elsewhere in the city, but still, in this city the need is pervasive, and worse, the people seem resigned.

It's really easy to forget the people in the underpass. They remain largely out of sight.

Boucherville

Di Jiang demonstrates the technique, then I spent some time practising my skills as a neurosurgeon using this device. This is at the NRC medical devices lab in Boucherville, Quebec. The glasses give me a 3D view, the tools are real, and when I touch the surface of the brain (in my case, to remove a tumour) I can feel the resistance of the flesh. It turns out, I'm a pretty good brain surgeon. And this type of application is a pretty good addition to our LPSS program. Even in online learning, there is no substitute for direct experience.

In Ottawa, and then in the Montreal suburb of Boucherville, I put together the pieces for my post Knowledge as Recognition. I had two objectives for this post. First, I wanted to draw out and explain what I meant by the theory specifically as a theory of knowledge (and not an expedient stepping stone on the way to some pedagogy). And second, I wanted to provide the students doing an assignment for a grade 12 philosophy course with an example of what (I thought was) good practice.

You can see how the two things come together. Experience builds what some people (mistakenly) call 'muscle memory'. What we are doing is literally reshaping the connections in our brain through multi-modal sensations, so that when we encounter a similar environment in the future, we will recognize the experience, and behave (more or less) automatically. Codification, representation and theory can help with the learning process, but they do not replace the learning process.

Berlin

Most people know that I was robbed on the Ubahn in Berlin, but once I began to restore my money and cards I once again enjoyed one of the most interesting cities in the world. I tried photograph the city using only the polarized lens (usually I'm shooting HDR, but without a tripod the shots aren't sharp) and while the results were pretty good, they still weren't what I wanted. But it's hard to work with light in a city shrouded in the dim gloom of December clouds. Live and learn.

My keynote at Online Educa, Reclaiming Personal Learning, was intended to challenge and provoke. I wanted education providers and vendors to understand that they no longer 'own' learners and their products. As a subtext I wanted to show how these companies draw and appropriate signs, symbols and meaning from the common culture, so I presented a slide show with photos taken exclusively from the conference tradeshow floor. From flowers to balloons to maps to people to little orange balls, the languages companies use to communicate with us is the language we have created and need to reclaim.

I summarized a number of talks at Online Educa, including the EPortfolios and Badges workshop, the Rheingold, Lewin and Stevenson keynotes, the debate on whether Data Corrupts Education, and the forum on Open Educational Resources.

It was in this context I introduced LPSS. I wanted to emphasize how LPSS was about people taking control over their own learning and owning their own data. I wanted to show that the same objections people have about companies like Facebook commoditizing personal data also apply to educational institutions and learning software vendors.And educational technology should not create closed silos of proprietary content, but instead should promote 'Ed Net Neutrality', enabling students to learn from whomever and how ever they wish.

People often associate poverty with crime. But I've had more trouble in wealthy nations than I've even had with the poor. I've been known in the past to say that wealth is the main prima facie indicator of criminality. Now I also wonder how much of the crime we attribute to the impoverished is simply them reclaiming what was once theirs.

Moncton

And so home again, back to the trees and the forests I see every day, back to small city living, snow and cold, back to my cats and my wife and my warm home, back to the day-to-day, of milestones and organization plans, budget forecasts and revenue expectations, back to designing networks, back to thinking about knowledge, inference, and discovery.

I had one more talk to give before the year would end, to my friends in Kerala, India, to whom I gave online a presentation called Developing Personal Learning. It was in part a review of the arguments of the preceding year, in part a sketch of a plan for the next, and in part the best I could offer only a few days after minor surgery in my mouth (a procedure called a 'gingival transplant').

On the flight home I authored a post on Open Education, MOOCs and Opportunities. It was intended to outline some of the background to what we're doing and to lay the groundwork for project work in 2015. I am hopeful we can more forward with these ideas. And in my post The OOC I laid out again the grounds for why I think that all elements of the MOOC are important, and why you can't just throw up a paywall or signing barrier and call a course open.

Halifax

Andrea and I finished the year in Halifax, where as we have for so many years (2014 was an exception) brought in the new year with Yuk Yuks comedy.

It's tempting to want to attribute something special to this year, to draw it all together with a theme, to attach meaning to it, but it was, ultimately, a year in the life, and was composed of the linked days and places, and not some grand design. As I looked through each of the 365 days, I looked at how much of what I did was the day-to-day, the mundane, the muddling thought. Even the highlights were as much by accident as by intention.

And some good things are happening just as the calendar changes over. People are questioning just what we learn from big MOOC data. Jon Dron found a really nice article outlining self-organizing distributed intelligence.

It was a year in which I was able to bring together and articulate so much of my thinking, expand on ideas, share my knowledge and experience, help develop capacity, bud some things, organize some things, help people and look forward to the future. A good year. I hope I was able to contribute something of value, whatever your objectives, wherever your world.

Saint John

Andrea and I began the New Year waking up in the port city of Saint John, just down the road from Moncton, where we had spent New Year's Eve watching a basketball game. Our basketball team is not a part of the family compact that owns so much of the industry in our province - to me it represents the future of the province, as something professional, independent, and based in the community. I'm willing to support the team because it's the sort of entity that doesn't just take - it gives back, and knows that without a reciprocal relationship it cannot survive.

I wrote the post Seven Real Signs of Surrender in response to an article that bemoans the commercialization of education but then defends the traditional role of professors and attacks open online learning. But from my perspective there's not much difference between professors pushing product on us or some commercial publisher doing it. The real signs of surrender are found in the passive deference of the university to the commercial imperative. To the extent that the professoriate is failing the community, it is signing the warrant for its own replacement.

Moncton

I spent the first three months of the year developing the core of my Personal Learning Framework presentation and sticking close to home, with a few quick trips to Ottawa and Montreal for meetings. It was a quiet time that allowed me to get in touch with the city again, get out into the winter countryside, focus more on my health and fitness, and throw myself into my new work for the year. More on that as we progress.

I do a number of online talks every year. This talk was delivered online to the Connecting Online for Instruction and Learning 2014 via WizIQ. In this talk, I noted that we are still in a world of mass, of masses of people, votes, ideas - we define ourselves by what we have in common with others, whether it is a language, a nationality, a religion or an idea. These are, I said, the properties of the individual, applied to the whole. It's the way we've always thought of thought, learning and society, as the spreading of an idea.

I think we should think of both learning and of society differently. The sameness isn't what creates learning and growth. The difference, the diversity is what does. It's the interaction that enables us to grow. We don't 'spread the word', we don't 'amplify' ideas - these are the signals we send to each other, but what defines us are the things we do, the way we relate to each other, and the outcomes we create. Ideas, learning culture and society emerge as a result of these transactions; they aren't transmitted through them.

These are hard ideas, but understanding them is key to understanding what works in education and society, what doesn't work, and how each should be structured to achieve the most positive outcomes.

Ashley and Taylor were interns observing as I had my teeth inspected and cleaned, and they were willing participants in my photo-a-day project. They illustrate a point that I've often made, that the best place to learn about some sort of work is in the workplace. And they're learning not by being told, but by seeing and experiencing (and later on, doing, while being observed by experts).

This is why it is important to consider carefully the sort of metrics we impose on open online courses, or indeed, any of our learning systems. Measuring 'course completion' is a poor substitute for watching and evaluating actual practice. I talk about this in my long interview with Juergen Rudolf, and we see it in the french-language course - MOOC-REL - we launched with the Organisation internationale de la francophonie and the Université de Moncton and in my discussion of the origin of the MOOC and theories related to connectivism.

Toronto

Rod and I were in town to meet with Defense department training coordinators, including people from the Canadian Defence Academy and DRDC. I gave them an internal government presentation on the Learning and Performance Support Systems program we were launching; these slides would form the theme for a lot of my talks through the rest of the year. It has been an interesting year for me because as program leader, I am responsible for the overall vision and direction of the program, as well as in attracting interest from potential commercial and institutional partners.

The discussions we had with defence and commercial partners at the meeting illustrate some of the tensions inherent in my own position and also in the nature of the technology we are trying to develop. The default position in education needs to be 'open', for a variety of reasons, and the military people get that, but the default position for them needs to be 'secure'. In a similar fashion, the business model needs to be cooperative, with companies engaged with institutions and students (and with us!) and not simply deriving income from them, but at the same time the bottom line for them is to sell, even in an inherently non-commercial marketplace.

I won't say I have the resolutions to these conflicts. But I think you have to start in the right place. I tried to get at that place with a few posts in February, including one on Economists and Education, and another on Where Government Money Comes From. I think we need to challenge some of the core presumptions about marketplaces - we need to question whether the measures and methodologies promoted by economists are sound (I would say the evidence of the last few years suggests they are not) and we need to question the 'inherent' efficiency of the business sector.

Valencia

I traveled to Valencia, Spain, to present The MOOC of One (text transcript) in which I tried to connect the phenomenon of massive open online learning to the concept of personal learning. The idea was to propose a system where providers offer services to many people, and where people access these services via their personal learning environment.

The presentation was also a challenge to the concept of representation. Traditional learning focuses on the idea that we share a common vision of things. This presentation emphasized the idea that each person's perception is unique. The traditional story of knowledge and perception involves the construction of models or representations, which we then share. But this supposes a separation between cognition and perception; it requires the idea that there is a 'camera' that we turn inward or outward to gather data which we will then interpret. But there is no camera. There is nobody to 'construct' our representations for us. Our perceptions are the result of self-organizing networks, an each one manages the task a little bit differently.

Valencia was beautiful, as expected. The old river bed has been converted into a city-wide park. I rented a bicycle and rode it end-to-end, first all he way out to the see, and then along the shore for several kilometers, and then back through the city centre and out to the open country on the other side. The city is an amazing mixture of old and new, of modern and decrepit, of prosperity and need. I talked about what it is to be One, to be a Valencian, to be a physicist, and the idea that there isn't some standard way to be any of these, but rather, to be one is to be shaped uniquely by the particular environment that is Valencia, or a physicist's lab, or one's own environment.

Tunis

This was my second trip to Africa and my third trip to an Muslim nation, though Tunis managed to be different from any of the preceding. It is a mixture of European influences (French is commonly spoken and the shops are closed on Sunday) and middle-Eastern cultures, with Arabic predominating, the influence of Islam everywhere, and the Adhan ringing out over the city, setting time to a clock that changes every day.

Speaking to an ALECSO board - that's the Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization - in a talk called The Rise of MOOCs I drew together the ideas of open resources, MOOCs and connectivism. In the MOOC part I outlined the history of our work with MOOCs, and then appealed to connectivism to inform the design principle underlying them. As described in connectivism, knowledge is the result of self-organizing networks, and so a MOOC (at least the way we design them) is designed to enable this self-organization process to occur.

So why the open resources? In order for a network to be able to function and to flourish, the entities within it need to be able to send signals from one to the other. These signals are send by means of the creation and sharing of open educational resources. Other approaches to education are focused on the idea that we should internalize or remember the contents of these resources. But connectivism is focused on the way the resources are used in order to create new resources.

Tunis is in the process of self-organization. It hasn't been easy. Important social functions (like street cleaning) have suffered. There are still security problems and so barriers and barbed wire can be an inconvenience. But the Souk is still open and there are products on the shelves. Transit is working, there are police in the streets. The people are getting on with the day-to-day task of living. Everywhere there is life and colour. Tunis, to my view, was a city breathing and learning and finding itself.

Carthage

In Carthage I walked along and undisturbed among the Roman ruins. The city is across a large bay from Tunis, over which, on a causeway, a rickety train runs a regular schedule. It was hot and it was dry and it was sometimes inconvenient to walk the distances between sites, but they gave me plenty of time to think. I saw a seaside park that had not been tended for a decade, a city that had not been lived in for a millennium, and everything in between, from the round harbours of the ancient city to the view from the park and mosque at the top of the hill. Carthage left me breathless.

Tourist buses take people from site to site. They skip the decrepit park, the museum of natural history, and the less accessible parts of the old harbours. There, from a tiny wood shack, a man emerged to tell me about the history of the harbour in broken French. I was the only visitor, perhaps for the day. Where we stood had been completely built up, with boathouses lining both sides. That was before the Romans razed it to the ground and then rebuilt over the same site. And before they too fell. I paid the man a fair price.